Wellingborough

Wellingborough (/ˈwɛlɪŋbərə/ WEL-ing-bər-ə) is a large market town in the Wellingborough district of Northamptonshire, England, 11 miles (18 km) from Northampton on the north side of the River Nene.[3][4]

| Wellingborough | |

|---|---|

Wellingborough Embankment on the River Nene | |

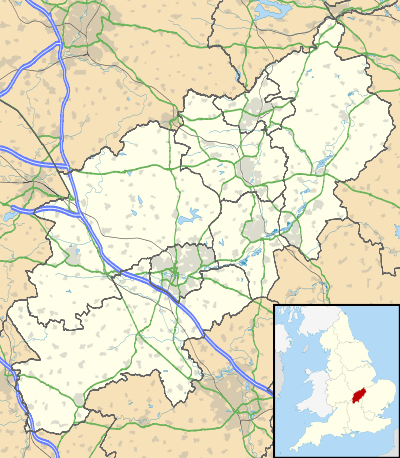

Wellingborough Location within Northamptonshire | |

| Population | 49,128 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP8967 |

| • London | 65 miles (105 km)[2] |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | WELLINGBOROUGH |

| Postcode district | NN8 NN9 |

| Dialling code | 01933 |

| Police | Northamptonshire |

| Fire | Northamptonshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www.wellingborough.gov.uk |

Originally named "Wendelingburgh" (the stronghold of Wændel's people),[5] the Anglo-Saxon settlement is mentioned in the Domesday Book as "Wendelburie". The town was granted a royal market charter in 1201 by King John.[6]

At the 2011 census, the town had a population of 49,128.[1] The Borough Council of Wellingborough has its offices in the town centre.[7] The town is twinned with Niort in France, and with Wittlich in Germany.

The town is predicted to grow by 30 per cent under the Milton Keynes South Midlands (MKSM) study, and the government has identified Wellingborough as one of several towns in Northamptonshire where growth in jobs and housing will be directed.[8] The area will see an addition of around 10,000 homes by 2031, mainly to the east of the town.[9] Wellingborough, along with Corby and Kettering together comprise the core of the North Northamptonshire growth area, coordinated by the North Northamptonshire Joint Planning and Delivery.[10] The town also has a growing commuter population as it is on the Midland Main Line railway, operated by East Midlands Railway, with trains to London St Pancras International taking under an hour, and an interchange with Eurostar services.[11]

History

The town was established in the Anglo-Saxon period and was called "Wendelingburgh". It is surrounded by five wells: Redwell, Hemmingwell, Witche's Well, Lady's Well and Whytewell, which appear on its coat of arms.[12]

The medieval town of Wellingborough housed a modest monastic grange – now the Jacobean Croyland Abbey – which was an offshoot of the monastery of Crowland (or Croyland) Abbey, near Peterborough, some 30 miles (48 km) down-river. This part of the town is known as Croyland.[13]

All Hallows Church[14] is the oldest existing building in Wellingborough and dates from c. 1160. The manor of Wellingborough belonged to Crowland Abbey Lincolnshire, from Saxon times and the monks probably built the original church.[15] The earliest part of the building is the Norman doorway opening in from the later south porch. The church was enlarged with the addition of more side chapels and by the end of the 13th century had assumed more or less its present plan. The west tower, crowned with a graceful broach spire rising to 160 feet (49 m), was completed about 1270, after which the chancel was rebuilt and given the east window twenty years later.[16] The church was restored in 1861 by Edmund Francis Law.[17] The 20th-century Church of St Mary was built by Ninian Comper.[18]

Wellingborough was given a Market Charter dated 3 April 1201 when King John granted it to the "Abbot of Croyland and the monks serving God there" continuing, "they shall have a market at Wendligburg (Wellingborough) for one day each week that is Wednesday".[6]

In the Elizabethan era the Lord of the Manor, Sir Christopher Hatton was a sponsor of Sir Francis Drake's expeditions; Drake renamed one of his ships the Golden Hind after the heraldic symbol of the Hatton family. A hotel in a Grade II listed building built in the 17th century, was known variously as the Hind Hotel and later as the Golden Hind Hotel.[19]

During the Civil War the largest substantial conflict in the area was the Battle of Naseby in 1645, although a minor skirmish in the town resulted in the killing of a parliamentarian officer Captain John Sawyer. Severe reprisals followed which included the carrying off to Northampton of the parish priest, Thomas Jones, and 40 prisoners by a group of Roundheads. However, after the Civil War Wellingborough was home to a colony of Diggers. Little is known about this period.

Wellingborough was bombed during World War II, on Monday 3 August 1942. Six people were killed and 55 injured; fortunately, being a bank holiday, thousands of people were away at a fair at a nearby village. Many houses and other buildings in the centre of the town were damaged in the attack.[20][21]

Originally the town had two railway stations: the first called Wellingborough London Road,[22] opened in 1845 and closed in 1966, linked Peterborough with Northampton. The second station, Wellingborough Midland Road, is still in operation with trains to London and the East Midlands. Since then the 'Midland Road' was dropped from the station name.[23] The Midland Road station opened in 1857 with trains serving Kettering and a little later Corby, was linked in 1867 to London St Pancras. In 1898 in the Wellingborough rail accident six or seven people died and around 65 were injured.[24] In the 1880s two businessmen held a public meeting to build three tram lines in Wellingborough, the group merged with a similar company in Newport Pagnell who started to lay tram tracks, but within two years the plans were abandoned due to lack of funds.[25]

Governance

Wellingborough is part of the Borough Council of Wellingborough which is, as of January 2018, a Conservative borough.[26] The borough council covers 20 settlements including the town together with Bozeat, Earls Barton, Easton Maudit, Ecton, Finedon, Great Doddington, Great Harrowden, Grendon, Hardwick, Irchester, Isham, Little Harrowden, Little Irchester, Mears Ashby, Orlingbury, Strixton, Sywell, Wilby, and Wollaston.[13]

The electoral wards in the town comprise:[13] Brickhill, Croyland, Hatton, Isebrook, Queensway, Redwell, Rixon, Swanspool, and Victoria; there are other, non-political division areas in Wellingborough such as: Gleneagles, Hatton Park, Hemmingwell, Kingsway, Queensway, Redhill Grange, and Redwell.

Wellingborough is part of the Wellingborough Constituency which includes the town, surrounding villages and other urban areas. The current MP is Peter Bone. Most wards in the Borough Council of Wellingborough are covered by the constituency and also include the wards in East Northamptonshire, the wards are: Bozeat, Brickhill, Croyland, Finedon, Great Doddington and Wilby, Harrowden & Sywell (excluding Ecton, Mears Ashby, and Sywell which all appear in the Daventry constituency due to overlapping parliamentary and local government boundary reviews), Hatton, Higham Ferrers Lancaster, Higham Ferrers Chichele, Irchester, Isebrook, Queensway, Redwell, Rixon, Rushden Hayden, Rushden Spencer, Rushden Bates, Rushden Sartoris, Rushden Pemberton, Swanspool, Victoria, and Wollaston.[26]

For European representation, Wellingborough is part of the East Midlands constituency with five MEPs.[27]

Geography

Geology

The town is sited on the hills adjoining the flood plain of the River Nene.[4][28] In the predominantly agrarian medieval period, this combination of access to fertile, if flood-prone, valley bottom soils and drier (but heavier and more clay-rich) hillside/ hilltop soils seems to have been good for a mixed agricultural base. The clay-rich hilltop soils are primarily a consequence of blanketing of the area with boulder clay or glacial till during the recent glaciations.[29] On the valley sides and valley floor however, these deposits have been largely washed away in the late glacial period, and in the valley bottom extensive deposits of gravels were laid down, which have largely been exploited for building aggregate in the last century.

Iron ore

The most economically important aspect of the geology of the area is the Northampton Sands ironstone formation. This is a marine sand of Jurassic age (Bajocian stage), deposited as part of an estuary sequence and overlain by a sequence of limestones and mudrocks. Significant amounts of the sand have been replaced or displaced by iron minerals, giving an average ore grade of around 25 wt% iron. To the west the iron ores have been moderately exploited for a very long time, but their high phosphorus content made them difficult to smelt and produced iron of poor quality until the development of the Bessemer steel-making process and the "basic slag" smelting chemistry, which combine to make high-quality steelmaking possible from these unprepossessing ores. The Northampton Sands were a strategic resource for the United Kingdom in the run-up to World War II, being the best-developed bulk iron-producing processes wholly free from dependence on imported materials. However, because the Northampton Sands share in the regional dip of all the sediments of this part of Britain to the east-south-east, they become increasingly difficult to work as one progresses east across the county.[30][31][32]

Iron ore quarrying was a major industry in and around Wellingborough from the 1860s until the 1960s. James Rixon and Wiliam Ashwell opened a major ironworks on the north side of the town in 1870, supplied by the extensive ironstone quarries around Finedon to the east of the town. Three narrow gauge tramways served the iron ore industry, the Wellingborough Tramway, Neilson's Tramway and the Finedonhill Tramway. The Wellingborough Tramway served Rixon's ironworks until 1966.[33]

Climate

Wellingborough experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification) which is similar to most of the British Isles.

| Climate data for Wellingborough, GBR | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13 (55) |

14 (57) |

17 (63) |

20 (68) |

24 (75) |

27 (81) |

29 (84) |

31 (88) |

24 (75) |

23 (73) |

17 (63) |

14 (57) |

31 (88) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7 (45) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

13 (55) |

17 (63) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

23 (73) |

19 (66) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

14 (58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

4 (39) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

8 (46) |

5 (41) |

3 (37) |

7 (44) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −15 (5) |

−13 (9) |

−8 (18) |

−5 (23) |

−1 (30) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

5 (41) |

4 (39) |

−3 (27) |

−10 (14) |

−14 (7) |

−15 (5) |

| Average precipitation cm (inches) | 4.51 (1.78) |

3.39 (1.33) |

2.87 (1.13) |

4.39 (1.73) |

3.49 (1.37) |

4.66 (1.83) |

4.21 (1.66) |

4.69 (1.85) |

5.49 (2.16) |

5.68 (2.24) |

4.8 (1.9) |

4.98 (1.96) |

53.16 (20.94) |

| Source: [34] | |||||||||||||

Compass

Wellingborough's nearest towns are Rushden, Higham Ferrers and Irthlingborough.

Demography

Wellingborough's population expanded rapidly from the 1960s and 1970s as agreements were signed between the Urban District Council and London County Council and the Greater London Council for the town to re-house over-spill population from London. Following the post World War II arrival of immigrants from the Commonwealth group of nations into Britain, a sizeable Black Caribbean and Indian/Pakistani community grew up in this small market town, and now represents 7% of the population in the Borough and to 11% within the town.[35]

Accent

The accent of a 21st century Wellingburian varies widely, the most common accent being very similar to London's, most likely due to the aforementioned London over-spill population, with elements and fusions of other ethnic accents, especially Jamaican. The fact that the town has a large Black Caribbean community significantly contributes to the accent.

Economy

Wellingborough has approximately 2,500 registered businesses within its boundaries.[36] Much of the town centre was redeveloped during the 1970s, when it grew rapidly from London overspill. The Borough Council has adopted a 'Town Centre Action Plan'.[37] The former traditional economic structure based on footwear and engineering is gradually diversifying with wholesale, logistics, and service sectors providing new opportunities for employment.

As a market town, Wellingborough has major high street chains mainly located in the town centre. The only shopping centre, Swansgate,[38] previously known as the Arndale Centre, was built in the 1970s. Since 2009 the Borough Council has been looking at rebuilding the centre[39] and major stores want bigger floor-spaces.[40] Supplementing the town centre shops are several out-of-town retail parks and supermarkets including a Sainsbury's,[41] four Tesco[42] stores, an Aldi[43] store and a Morrisons[44] store in the town centre. The town has a market three times a week and a weekly privately organised market.[6]

Other businesses operating within the town include motorsport, high performance engineering, distribution, engineering, environmental technology and renewable energy, digital and creative media, financial and business services, and global brands, once such brand being Cummins UK at Park Farm, major park home manufacturer Tingdene Homes Ltd at Finedon Road Industrial Estate and Lok'nStore Plc. There are several industrial estates in the town, these include Park Farm,[45] Denington,[46] Leyland[47] and Finedon Road.[48]

- Future developments

As part of its Milton Keynes South Midlands (MKSM) study, the government has identified Wellingborough as one of several towns in Northamptonshire into which growth will be directed over the next thirty years. It allocates 12,800 additional homes to Wellingborough, and will also create additional facilities, further improve the town centre, improve infrastructure and increase employment opportunities. A jobs growth target of 12,400 jobs has been set to accompany the large scale housing growth.[49] A plan for 3,000 homes north of the town has been accepted by the British Government after an appeal by Bee Bee Developments. The plan was first refused by Wellingborough Borough Council.[50]

As a result, plans have been made for a major urban extension in the town, mainly to the east of the railway station. When finished, the town would be around 30% larger and 3,200 new homes would be built on 'Stanton Cross' site, with new schools, bus stops, community centres, shops, a doctor's surgery and new open spaces.[51] The railway station would be developed into an 'interchange' with local buses and trains. The upgrade would provide a new platform, footbridge and new station buildings.[52] Outside the station a new road bridge from Midland Road over the railway line is also planned with a new footbridge to reach the new development.[53] Other plans to include the development of the High Street, Shelley Road and the north of the town areas are also being considered.[54][55]

Transport

The A45 dual carriageway skirting to the south, links the town with the A14, and M1 which also allows links to the east and west of the country. The A45 links Wellingborough with Northampton, Rushden, Higham Ferrers, Raunds, Thrapston, Oundle and Peterborough.

The town is served by a bus network provided by Stagecoach in Northants, Centrebus with local Wellingborough buses the W1, W2 and W8 links the town centre (Church Street) with local suburbs and villages.[56] Departing every 30 minutes the X4 service also links the town with Milton Keynes, Northampton, Kettering, Corby, Oundle and Peterborough.[57] Other routes include 44/45, X46 and X47.[56]

East Midlands Railway operate direct trains to London St Pancras International from Wellingborough railway station, departing every 30 minutes, with an average journey time of around 55 minutes.[58] The railway line also connects Wellingborough with Bedford, Luton, Kettering, Corby, Leicester, Nottingham, Derby, Sheffield and Leeds. Just north of the railway station is a GB Railfreight location, usage is for London Underground maintenance and other freight services.[59]

Several UK airports are within two hours' drive of the town, including London Luton, East Midlands, Birmingham and London Stansted. Luton can be reached directly by train while East Midlands and Stansted can be reached by one change at Leicester. Sywell Aerodrome, located 5 miles northwest of Wellingborough, caters for private flying, flight training and corporate flights.

Education

Fourteen government controlled primary schools feed the secondary schools that include: Wellingborough School, an independent, fee-paying school with a cadet force, and the state secondary schools of Sir Christopher Hatton School, Weavers Academy (formerly the Technical Grammar School & then Weavers School), Wrenn School (formerly the Wellingborough Grammar School) and also gives home to the local Sea Cadet Unit, and Friars School.[60]

The Tresham College of Further and Higher Education has a campus in Wellingborough, as well as locations in Kettering and Corby.[61] It provides further education and offers vocational courses.[62] In collaboration with several universities the college also offers Higher Education options.[63]

The University of Northampton in Northampton, with around 10,000 students on two campuses, offers courses from foundation and undergraduate levels to postgraduate, professional and doctoral qualifications. Subjects include traditional arts, humanities and sciences subjects, as well as entrepreneurship, product design and advertising.[64]

Culture

The Castle Theatre was opened in 1995 on the site of Wellingborough's old Cattle Market.[65] It brings not only a theatre to the area but other facilities for local people. Most rooms are used on a daily basis by the local community, users include the Castle Youth Theatre[66] and Youth Dance.[67]

Wellingborough has a public library in the corner of the market square.[68] The Wellingborough Museum,[69] an independent museum run by the Winifred Wharton Trust, located next door to The Castle Theatre, has exhibitions which show the past of Wellingborough and the surrounding villages. The museum is housed in a Victorian swimming pool ("Dulley's Baths") built in 1892, from 1918 to 1995 it was Cox's shoe factory. Accompanying the exhibitions and articles is a souvenir shop and café.[70]

Sport

Wellingborough is home to two football clubs: Wellingborough Town[71] and Wellingborough Whitworth.[72] From 14 April 1928 a short lived, small independent (not affiliated to the sports governing body) greyhound racing track was opened around the football pitch at the Dog and Duck Ground.[73]

In 2009 the town's rugby club was the first club to be awarded the RFU Whole Club Seal of Approval in the East Midlands.[74] Harrowden Hall, a 17th-century building in Great Harrowden village just on the outskirts of the town, is the clubhouse of a privately owned golf course.[75] The four leisure centres and health clubs in Wellingborough include Bannatyne's, Redwell, Waendel and Weavers (which is part of Weavers school).[76]

Wellingborough was also served for many years by Club Diana. Club Diana was closed by administrators on 1 June 2011.[77] However it has now been reopened and is available once again. It has a swimming pool, 5 squash courts and a bar and restaurant.

The Waendel Leisure Centre is the main council-owned leisure centre in Wellingborough. The facility includes a six-lane 25-metre competition pool, varying in depth from 1 to 2 metres, and used for many purposes including the main training pool for Wellingborough Amateur Swimming Club. The pool is regularly used for small competitions, as other than Corby Pool it is the only other aptly equipped facility – boasting new starting blocks, as well as an integrated timing system and time board. The pool also has a small, shallow, 'teaching' pool, more suitable for non-swimmers. Waendel also operates a newly refurbished gym on the upper level.[78]

Waendel and Redwell Leisure Centres are both owned by Wellingborough Borough Council, however are operated on their behalf by Places for People. Waendel pool is currently in need of urgent repairs due to tiles coming away from the pool floor.[79]

Wellingborough Phoenix is one of the United Kingdom's largest basketball clubs; the men's first team currently play in EBL Division 3 and the women play in EBL Division 2. Youth teams also play in the EBL; ages ranging from u13 to u16.[80]

On the second weekend in May, the annual non-competitive Waendel Walk is held in Wellingborough, with a variety of routes through the local countryside. The walk is affiliated to the International Marching League.[81][82]

Services

Several NHS centres provide health care facilities, with Isebrook Hospital being equipped for procedures such as large X-Rays and neurological investigations, and long-term care, that are not catered for by primary care surgeries. Accident & Emergency (A&E), maternity,[83] and surgical issues are mainly covered by Kettering General Hospital. The Air Ambulance is provided by Warkshire and Northamptonshire Air Ambulance service.[84] A petition signed by thousands of local residents in the towns of Wellingborough and Rushden for a new A&E to be built in Wellingborough has been handed to 10 Downing Street (when Prime Minister Gordon Brown was in power), by local MP Peter Bone on 10 February 2010.[85]

Other emergency services are provided by the Northamptonshire Fire and Rescue Service and the Northamptonshire Police. Wellingborough Prison was located just outside the town, but closed in 2012, however it is currently being rebuilt.

Landmarks

The railway station is a Grade II Listed building, and among the many unusual and other listed buildings in Wellingborough is the 600-year-old Grade I listed steeple that forms part of All Hallows Church.

The Three Silver Ladies is one of two identical sculptures installed on the Harrowden Road, They depict local Roman history, the river, and the townspeople working together.[86]

Wellingburians

Wellingborough is the birthplace and residence of many notable people, including the former world champion snooker player Peter Ebdon, and Sir David Frost, OBE, a broadcaster who attended Wellingborough Grammar School, whose campus is now occupied by the Wrenn School.[87] The winner of Britain's Strongest Man contest in 2002, Marc Iliffe, lived in the town.

Scientist Kenneth Mees, and Frederic Henry Gravely an arachnologist, entomologist, and zoologist were born in the town. Paul Pindar, an ambassador of King James I to the Ottoman Empire, was born and grew up in the town, and attended Wellingborough School.

The town has sports people such as Rory McLeod and[88] Jamie O'Neill both snooker players, born in the town,[89] and football players Trevor Benjamin[90] and Bill Perkins both grew up in the town. Perkins played for a number of teams including Liverpool Football Club, Kettering Town and Northampton Town.[91] Fanny Walden was born in the town, formerly playing for Northampton Town and Tottenham Hotspur. Brian Hill, referee, was also born in the town. Anita Neal, 100 m olympic sprinter, lived in the town and went to John Lea School[92] England Rugby captain Bob Taylor and player Jeff Butterfield both taught at Wellingborough Grammar School. Infamous football hooligan colloquially known as the Pig of Marseille is also from the town.[93]

Wellingborough is home to singers Peter Murphy of Bauhaus who lived a large portion of his early life here, and Thom Yorke of Radiohead. Politicians Alfred Dobbs, Arthur Allen (for the Labour Party) and Brian Binley (for the Conservative Party).

Wellingborough is also the residence for British YouTube personality, professional gamer and Youtuber DanTDM who attended Weavers School 2003-2008 and continued into the Sixth Form for two years.[94]

Authors connected with the town include Lesley Glaister who was born in Wellingborough, while Stephen Elboz was born and currently lives in the town.[95] Journalist and whisky writer Jim Murray also lives here. Author and historian Bruce Quarrie lived in the town before his death in 2004. A school in Wellingborough is named after Sir Christopher Hatton, and high scoring World War I fighter pilot Edward Mannock (Major 'Mick' Mannock) lived in the town and is mentioned on the Wellingborough War Memorial and has a road named after him.

Twin towns

Wellingborough is twinned with:

and also has relations with Willingboro, township in Burlington County, New Jersey, United States,[96] while Irchester and Grendon, two of the villages within the Borough of Wellingborough, have twin town partners at Coulon near Niort, and Bois-Bernard near Arras.[96]

See also

- Redhill Grange, a suburb in Wellingborough

- Wellingborough (borough), The Borough Council of Wellingborough

- Wellingborough (UK Parliament constituency)

- Grade I listed buildings in Wellingborough (borough)

- Grade II* listed buildings in Wellingborough (borough)

References

- UK Census (2011). "Local Area Report – Wellingborough Built-up area (1119885015)". Nomis. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- Whatley, Stephen (1751). England's Gazetteer. 2. J. and P. Knapton.

- Google Maps: Wellingborough. Retrieved 29 January 2010

- Northamptonshire flood plains. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Mills, David (2011). A Dictionary of British Place Names. Oxford: the University Press. ISBN 9780199609086.

- Wellingborough Market. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough Location map. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Milton Keynes Council (August 2009). "MKSM Research Project- Economic Development Evidence Base Final Project" (PDF).

- Wellingborough, Borough Council of. "Borough Council of Wellingborough download - North Northamptonshire Development Company - Programme for Development | Environment and planning". www.wellingborough.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "Delivery". www.nnjpdu.org.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- East Midlands Trains: Interchange with Eurostar. Retrieved 2 March 2010 Archived 18 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Explore Northamptonshire: About Wellingborough Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough: Councillors by Wards. Retrieved 7 July 2017

- All Hallows Church Archived 28 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 August 2009

- Crowland Abbey. Retrieved 21 August 2009

- All Hallows Church: History Archived 28 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 26 February 2010

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (1961). The Buildings of England – Northamptonshire. London and New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 451. ISBN 978-0-300-09632-3.

- Architect Design: St Mary's Wellingborough. Retrieved 23 August 2009

- Historic England. "The Golden Hind Hotel (1286782)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Enjoy Northamptonshire's Heritage: The Second World War". Northamptonshire County Council. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- "Roll of Honour: Northamptonshire - article in the Mercury & Herald Northampton, 7 August 1942". British Legion. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Subterranea Britannica: Wellingborough London Road

- Radford, B (1983). Midland Line Memories: a Pictorial History of the Midland Railway Main Line Between London (St Pancras) & Derby. London: Bloomsbury Books.

- Railway Archive: Wellingborough Rail Crash. Retrieved 24 January 2010

- The Northants Evening Telegraph, 'Millennium Memories', Saturday 1 January 2000, ISBN 0-9502845-1-3

- Wellingborough Conservatives. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- UK Office of the European Parliament: East Midlands MEPs Archived 7 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine Access Date 2 March 2010

- Wellingborough Geology Map Archived 20 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Borough Council of Wellingborough: Northamptonshire Geology Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 11 June 2010

- Northants Geology Map Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- [ Northamptonshire Jurassic age]. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Mike Lewis. "The Geology of Northamptonshire". Department of Geography and Geology, Northamptonshire Grammar School. Archived from the original on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- Quine, Dan (2016). Four East Midlands Ironstone Tramways Part Three: Wellingborough. 108. Garndolbenmaen: Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railway Modelling Review.

- "Average weather for Wellingborough". Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough: Population Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 August 2009

- Connected Wellingborough: Opportunities. Retrieved 12 June 2010

- Growth in Wellingborough. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Swansgate Shopping Centre Archived 29 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough: Rebuilding Swansgate. Retrieved 20 April 2010

- Northants Evening Telegraph: Big-names too large for town. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Sainsbury's: Wellingborough Store. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Tesco: Store Locator. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Aldi: Wellingborough store. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Morrisons: Wellingborough store. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Borough Council of Wellingborough: Park Farm industrial estate Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Borough Council of Wellingborough: Denington industrial estate Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Whittle Jones: Leyland Trading Estate – Formally the British Leyland Foundry and Manufacturing Plant, until its closure in September 1981. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- Borough Council of Wellingborough: Finedon Road industrial estate. Retrieved 30 January 2010

- North Northants Development Company Archived 17 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Cleaver, Monique (11 February 2010). "Green light for 3,000 new homes". Northants Evening Telegraph. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough Housing Strategy (PDF) Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 23 August 2009

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough: Growth Area Development May 2009. Retrieved 20 April 2010

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough: Growth Area Fact Sheet 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2010

- Wellingborough planning. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- "Wellingborough 2020 Vision: A strategy for regeneration and growth in Wellingborough". Borough Council of Wellingborough. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- [Northamptonshire County Council: Buses in Wellingborough & East Northants Map]. Retrieved 26 July 2013

- Stagecoach Northants X4. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- East Midlands Trains: Midland Main Line Timetable. Retrieved 26 July 2013

- GB Railfreight: Locations, Wellingborough Archived 11 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2010

- Northampton County Council: Map of Schools Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Tresham College: Our Campuses Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009

- Tresham College: Our Courses. Retrieved 8 August 2009

- Tresham College: Higher Education Archived 19 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 8 August 2009

- The University of Northampton: About Us. Retrieved 8 August 2009

- Castle Theatre: History Archived 29 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 21 March 2010

- Castle Theatre: Youth theatre Archived 29 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2010

- Castle Theatre: Youth dance Archived 29 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 March 2010

- Northamptonshire County Council: Wellingborough Library. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Wellingborough Museum's website Archived 8 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 19 June 2010

- Wellingborough Museum entry on Culture24. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Wellingborough Town F.C.. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Wellingborough Whitworth. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- "Wellingborough". Greyhound Racing Times. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- Wellingborough Rugby Football Club Archived 30 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 14 January

- Wellingborough Golf Club. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- The Borough Council of Wellingborough: Leisure centres. Retrieved 28 January 2010 Archived 18 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Town fitness club in administration – Top Stories – Northamptonshire Telegraph. Northantset.co.uk (31 May 2011). Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- Weaver, Stephanie. "Major refurbishment for Waendel and Redewell Gyms in Wellingborough". Northamptonshire Telegraph. Johnston Publishing. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- Weaver, Stephanie. "Urgent repair work needed at Wellingborough pool". Northamptonshire Telegraph. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- English Basketball League

- "IML Walking Association Event. Waendel Weekend".

- "International Waendel Walk". Borough Council of Wellingborough.

- NHS: Maternity Details. Retrieved 28 January 2010

- Warkshire and Northamptonshire Air Ambulance. Retrieved 2 March 2010

- Goodjohn, Bernie (10 February 2010). "Petition handed over for hospital". Northants Evening Telegraph. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- Geograph. Retrieved 24 June 2010

- Tall, David & Graham (2006) Memories of Wellingborough Grammar School Foreword by Sir David Frost Archived 6 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- The Independent. Retrieved 24 February 2010

- Global Snooker Centre. Retrieved 25 February 2010 Archived 3 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Northants Evening Telegraph: Transfer Talk. Retrieved 25 February 2010

- IFC History:Bill Perkins. Retrieved 25 February 2010

- Rushden Heritage. Retrieved 25 February 2010

- "Euro 2016 travel ban for 'Pig of Marseille' James Shayler". BBC News. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- "Dan Middleton's Minecraft videos a global hit". BBC News. 11 April 2014. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- Oxford University Press: Stephen Elboz. Retrieved 25 February 2010

- Town twinning.. Retrieved 17 June 2010

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wellingborough. |

- Borough Council of Wellingborough

- Northamptonshire county council

- Northants Evening Telegraph

- BBC Northamptonshire

- Explore Northamptonshire The Official Northamptonshire tourism website.